“Boris Johnson would have been denied a majority in parliament if the UK had used the voting system adopted for European parliament polls at the general election, new research shows,” says The Independent (14/12/19]

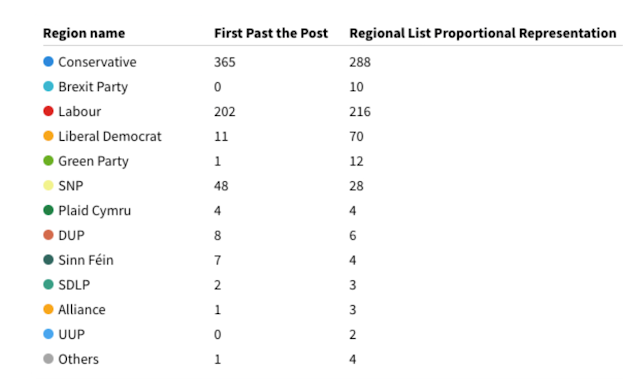

They cite analysis by the Electoral Reform Society that suggests that under PR the Conservatives would have been unable to achieve a majority. Whilst Labour would have done marginally better the big winners would have been the Lib Dem’s, Greens and the Brexit Party. The main losers would have been the Conservatives and the SNP. Whilst it is tempting to see this outcome as desirable, it is worth considering whether it is fairer or more democratic.

The Electoral Reform Societies view is that “Westminster’s voting system is well and truly broken.” Given that our current system produces landslide victories for a party for which well over half of the population did not vote this seems a valid statement.

Advocates of PR, who tend to be supporters of parties who would benefit from it, point to the fact that votes per seat show a huge disparity between the parties. This is undoubtedly the case. Each Conservative seat was won with just over 38,000 votes, whilst Labour had to amass over 50,000 votes to win a seat. And, if that seems prima facie unfair, then consider that the Greens had to get over 860,000 votes for each seat (which Caroline Lucas did in Brighton, of course). The poor Lib Dem’s needed over 300,000 votes for each seat.

All of which seems to support a view that we need PR to make the system fair. But, and this is I believe a major flaw in the PR argument, this supposes that we are voting for a party and not a representative. If, like me, you were outraged when MP’s from both Labour and Conservative decided they no longer liked their party and simply joined (or started) another one and thought this undemocratic you fell into a well worn constitutional trap. Many people signed the petition calling for an immediate by-election in such cases. If so, you will recall the Government response:

“Formally, electors cast their vote for individual candidates, and not the political party they represent. The Government does not plan to change this constitutional position.”

Formally, of course, that is the case, but in reality we all know that party loyalty is equally as important, perhaps more so, than which individual has secured their party’s nomination. In the Hansard Society’s Audit of Political Engagement only 22% could name their MP. Unfortunately, they stopped asking this question in 2013 so the degree to which MPs remain anonymous to those who vote for them is difficult to gauge. It seems unlikely, however, that much has changed.

In the latest Audit (2019) the Society found that 72% of their sample felt the political system needed improving. That figure tends to support some form of PR, but since they were not asked how it should be improved that should not be taken as read. To be fair, a poll carried out by ICM for Make Votes Matter in 2017 did find widespread support for PR with 61% agreeing with this statement:

“Proportional representation is the collective name given to electoral systems which ensure that the proportion of seats a party receives in Parliament closely reflects the proportion of votes they received from voters. Currently, the UK uses a system known as ‘First-Past-The-Post’ which does not ensure that a party’s share of the seats matches the share of the votes. In principle, would you support or oppose changing the electoral system from First Past The Post to a system of proportional representation?”

“Proportional representation is the collective name given to electoral systems which ensure that the proportion of seats a party receives in Parliament closely reflects the proportion of votes they received from voters. Currently, the UK uses a system known as ‘First-Past-The-Post’ which does not ensure that a party’s share of the seats matches the share of the votes. In principle, would you support or oppose changing the electoral system from First Past The Post to a system of proportional representation?”

I am a democrat. I am also a member of the Labour Party. I have a visceral dislike and distrust of the Tories. However, just because a different system would make it likely that they would not form a government in future does not seem to me to be a good enough reason to support it.

My opinion, for what it’s worth, is that the current system is broken. However, the problem is not representation per se, but the overlaying of a party system on a system of representation. That so few people know the name of their MP is hardly surprising. At election times we are encouraged to think in terms of which party we prefer, and even more narrowly which prime minister.

When we go to vote we are told the names of the candidates and their party affiliation. No matter how strong a local candidate if they do not have the support of one of the major parties they do not stand any chance of being elected. One very simple reform could fix this and return our elections to the contest for particular constituencies: the only information on the ballot paper should be the name of the candidate.

Such a reform would, without any major cost, bring about a major change in our political culture. In future no candidate, even those in safe seats, would be able to assume that they would get in purely because of party affiliation. They would have to canvass on their own name and ensure that electors were prepared to vote for them. Electors would be encouraged to judge candidates on their character and politics. The media could no longer turn politics into a party game where high profile politicians steal all the oxygen and “low level” local politicians rarely get a mention.

This reform, on its own, would shift the emphasis away from parties but it would not abolish parties, neither would such a move be desirable. Candidates would still ally themselves to political parties and parties would still have a machinery that would grind into action at election times. The difference would be that parties would genuinely have to engage in all constituencies, rather than run a UK-wide operation.

I would favour a second reform that would make the competition in all these constituencies manageable. At the moment we have two types of elections for Westminster: General Elections and by-elections.

Why is it necessary to contest all 650 seats at the same time? During a General Election we have 5 weeks of frantic activity and intense trivialisation of the issues. Would it be preferable to have, say, 4 year terms and elect ¼ of the MP’s each year?

I can see the objection to this in it meaning that we would be fighting elections constantly and people might get fed up with them. But, Brenda from Bristol would only get one Parliamentary Election every 4 years, barring a by-election. The media rather than fixating on Westminster might be able to cope with travelling to other parts of the country once a year and concentrating on the local candidates rather than obsessing over whatever fresh political gossip was emerging from their unnamed sources (shorthand, we now know, for the Tories Press Office).

The other obvious objection, I’m sure there are others, is that we would have no settled government. Each year the party in government could lose its parliamentary majority. This is true, but surely this would encourage government, of all hues, to be cognisant of public opinion when proposing legislation. A successful government would just as easily increase its majority as lose it.

Incidentally, if we really want to stop the spread of fake news that would be easily achieved by cutting it off at source. Unless a case can be made for national security or for somebody’s life being at risk, there should be no stories in the press or broadcast media that come from unnamed sources. Additionally, if we want to see a rise in political engagement both press and broadcast media should be under a legal liability to be impartial and fair. Though quite how that is to be adjudicated might take a bit of working out.

I can hear the rumblings from the back: what about proportional representation? Any reforms to our present system (and, to be honest, any reforms under the Johnson administration are likely to involve less democratic accountability rather than more) must be seen in light of some of the other findings from the Hansard Society.

In their most recent report they found that 42% think many of the country’s problems could be dealt with more effectively if the government didn’t have to worry so much about votes in Parliament. In other words, the failures of the Brexit debacle are being seen by a large number of British people as evidence that parliamentary democracy itself is the problem.

The most worrying conclusion is that a drift towards authoritarian rule can be seen in the fact that 27% strongly agreed that “Britain needs a strong leader prepared to break the rules”, a further 27% somewhat agreed. Now, to be clear, the research never asked what exactly they thought “breaking the rules” might entail or, perhaps more pertinently whether they thought breaking rules which protect their own interests would be desirable.

In an article in The Guardian (20/06/17) academics Maria J Stephan and Timothy Snyder argued that democracy was being pushed back across the globe by authoritarian regimes that relied on popular support. They were thinking of Trump, Oban, Erdogan and Maduro. But, we should probably now add Johnson to the list. Their advice was to build strong, non-violent, civil resistance. As they put it:

“Authoritarians thrive on popular fear, apathy, resignation, and a feeling of disorientation. Movement leaders need to assure people that their engagement and sacrifices will pay off, something Solidarity leader Adam Michnik understood well: ‘Above all, we must create a strategy of hope for the people, and show them that their efforts and risks have a future.’”

|

| A right to rule for life? |

It is the election of the second chamber that I believe should be elected on a party basis and by proportional representation. It’s function, much as now, would be to oversee the Commons and hold the government to account. Party’s would receive seats proportionate to their vote share in an election which, in my opinion, should not be run in tandem with any other election.

This would allow the electorate to choose a second chamber either to push through the policies of a popular government or to act as a balance against a government which was pursuing unpopular policies. As now, there would need to be checks and balances to ensure that the business of governing could get done but the argument for more accountability and the undermining of privilege and elitism is long overdue.

I am under no illusion as to the possibility of democratic reform in the short term, but clearly it must be in the interests of those who consider themselves democrats to want to bring our democratic institutions into line with the century in which they are asked to perform. That so few people trust either our institutions or our politicians is a major failing of our democratic processes, and points to a need for reform. The current crisis of democracy is not just to be seen in the corruption, deceit and cronyism at the heart of the political system, but in the ever receding faith that ordinary people have in both politics and politicians. Fixing that requires not strong leaders who break rules but rather a system that is responsive to, and accountable to, the voters whose lives are affected by the decisions made in Westminster.

I

I