We tend to think of democracy as a good thing, the type of thing we can all support. There is a sense in which everybody in so-called democratic countries knows what is meant by democracy. In essence, it is the idea of rule for the people by the people. This involves universal suffrage, representation, all votes being equal, the rule of law and decisions taken by democratic consensus.

So ingrained are these ideas that it is difficult to believe that, in a democracy, there are people who see democracy in slightly different terms. For some people democracy is a fine system if, and only if, it delivers for them, and their class, that which they desire.

We take democracy for granted. But it has not always been that way. Universal suffrage was only conceded in the UK in 1918, and even then only for those over 30. Full suffrage for every adult citizen (those 18 or above) did not arrive until 1970.

The fight for the vote was initially fought not by working people but by those who wanted political power to match their economic power – landowners, merchants and factory owners. Their idea of democracy was to have the right to pass laws which kept the working class firmly in its place.

Some people would have us believe that the right to vote was granted because the dominant economic classes were liberal and fair minded. If only that were the case. The truth is that every concession to universal suffrage was conceded only after mass campaigns and as a means to prevent working class people from taking control. Revolution not evolution has been the key to all suffrage movements.

|

| Factory owners oppose any reforms even those designed to protect children |

If that seems unlikely to you then just consider how the same economically dominant classes have resisted all attempts to make working people’s lives better. Every minor concession from reducing the working week, to holidays, to health and safety regulations, to the minimum wage has been met with hostility by those who profit most from the labour of ordinary people.

Interestingly enough, if you search the internet for references to how hostile employers were you cannot find it. The past has been sanitised so that we remember the names of pioneering liberals such as Edward Chadwick who worked to improve conditions but find little reference to those who opposed the acts.

When the last Labour Government proposed a minimum wage

of £3.60 many commentators suggested that it would mean a

reduction in jobs. Fast forward to 2019 and Labour’s policy of

a £10 minimum wage is met by Paul Johnson of the Institute for Fiscal Studies claiming “Clearly, the risk, given the choice between doubling the wages you’re currently paying 16 and 17-year-olds or not employing them at all… the risk is you will have fewer 16- and 17-year-olds in work.”

In other words conventional wisdom is that any attempt to democratically increase the pay of workers will be met not with their active resistance but by businesses deciding not to do the work at all. That even Philip Hammond, when still Chancellor, had to concede that job losses predicted by those opposed to a minimum wage failed to materialise is evidence of the way the economically dominant class use their parliamentary advantage to work hand in glove with their acolytes in civil society, particularly the media which feeds off the type of “think tanks” represented by the likes of Paul Johnson, who earns upwards of £129,000 somewhat more than £10 an hour.

If that seems far fetched ask yourself how often are trade unions represented in discussions about workers rights? And, when they are, how close are those we know – such as Len McLuskey – to the real lived experiences of ordinary workers?

We are taught from a young age to believe that we live in a society where everybody has an equal vote and by extension an equal say. But this is plainly untrue. Not all votes are equal, because somebody such as Paul Johnson, and we could add other commentators, have not just a vote but an unfair advantage in their

access to opinion forming forums.

What this results in is a public discourse totally

dominated by the concerns of the middle and upper classes. Or to put that more simply we live in a society where those who gain most from the current economic arrangements also control the opportunity to critique that system.

As Marx once wrote: “The class which is the ruling material force of society, is at the same time its ruling intellectual force. The class which has the means of material production at its disposal, has control at the same time over the means of mental production, so that thereby, generally speaking, the ideas of those who lack the means of mental production are subject to it.”

This is not to say that countervailing arguments never see the light of the day. In a liberal, parliamentary democracy opposing views are allowed, even encouraged, but within tightly controlled parameters. Democracy is not for debate, neither is the basic functioning of the economy.

Interestingly enough, if you search the internet for references to how hostile employers were you cannot find it. The past has been sanitised so that we remember the names of pioneering liberals such as Edward Chadwick who worked to improve conditions but find little reference to those who opposed the acts.

When the last Labour Government proposed a minimum wage

of £3.60 many commentators suggested that it would mean a

reduction in jobs. Fast forward to 2019 and Labour’s policy of

a £10 minimum wage is met by Paul Johnson of the Institute for Fiscal Studies claiming “Clearly, the risk, given the choice between doubling the wages you’re currently paying 16 and 17-year-olds or not employing them at all… the risk is you will have fewer 16- and 17-year-olds in work.”

In other words conventional wisdom is that any attempt to democratically increase the pay of workers will be met not with their active resistance but by businesses deciding not to do the work at all. That even Philip Hammond, when still Chancellor, had to concede that job losses predicted by those opposed to a minimum wage failed to materialise is evidence of the way the economically dominant class use their parliamentary advantage to work hand in glove with their acolytes in civil society, particularly the media which feeds off the type of “think tanks” represented by the likes of Paul Johnson, who earns upwards of £129,000 somewhat more than £10 an hour.

If that seems far fetched ask yourself how often are trade unions represented in discussions about workers rights? And, when they are, how close are those we know – such as Len McLuskey – to the real lived experiences of ordinary workers?

|

| The myth that every vote is equal pervades our culture |

access to opinion forming forums.

What this results in is a public discourse totally

dominated by the concerns of the middle and upper classes. Or to put that more simply we live in a society where those who gain most from the current economic arrangements also control the opportunity to critique that system.

As Marx once wrote: “The class which is the ruling material force of society, is at the same time its ruling intellectual force. The class which has the means of material production at its disposal, has control at the same time over the means of mental production, so that thereby, generally speaking, the ideas of those who lack the means of mental production are subject to it.”

This is not to say that countervailing arguments never see the light of the day. In a liberal, parliamentary democracy opposing views are allowed, even encouraged, but within tightly controlled parameters. Democracy is not for debate, neither is the basic functioning of the economy.

The holy trinity in all this are the tenets which are so taken for granted that we find them impossible to challenge without being labelled extremist: parliamentary democracy, a free press and a free market economy. The guardians of this system are the private schools which educate just 7% of the population. That 7% are embedded throughout the trinity of Parliament, media and economy. In 2017 some 29% of MPs were privately educated a figure which rises to 45% among the ruling Conservative Party. Remember only 7% of the population are privately educated so they are 4 times more likely to be MPs than their actual numbers suggest they should be.

|

| If you areprivately educated you are 10 times more likely to be a judge than if you are state educated. |

The Press Gazette reported in June this year that 43% of the top 100 editors were privately

educated. Whilst the Guardian revealed that in television the workforce is more than twice as likely than in other professions to be privately educated. Ofcom said the evidence suggested that the TV industry was disproportionately recruiting people from private school backgrounds. This means that political commentary in the papers and on TV disproportionately represents the assumptions of the privately educated.

Meanwhile The Guardian also reported in 2016 that a privately educated elite continues to dominate the UK’s leading professions, taking top jobs in fields as diverse as the law, politics, medicine and journalism, according to research. This includes 74% of top judges, 51% of print journalists, 61% of top doctors, and even in the arts 43% of BAFTA winners were privately educated.

All of this adds up to a social system that works very well for a small section of the population. And, in case, you are tempted to think that electing a Labour Government will change this, it will not.

As Aneurin Bevan said in 1954:

“I know that the right kind of leader for the Labour Party is a kind of desiccated calculating-machine

who must not in any way permit himself to be swayed by indignation. If he sees suffering, privation

or injustice, he must not allow it to move him, for that would be evidence of the lack of proper

education or of absence of self-control. He must speak in calm and objective accents and talk about a dying child in the same way as he would about the pieces inside an internal combustion engine.”

And, until 2016 that is precisely the kind of leader we have had. The point is not that we cannot have a different type of leader, or radical policies but that democracy is being undermined not just in parliament but, as it always has, by the media, the judiciary, and by those who benefit from the iniquities of the current economic system.

That Boris Johnson and his attack dog Fido Cummings have a distaste for parliamentary democracy and recently the judiciary too, is not proof that democracy is under threat. Indeed, the democratic deficit is not between the Tories and Labour (far too many Labour MP’s are supporters of the current social system) but as it has always been, between a class that rules and a class that is subject to those rules.

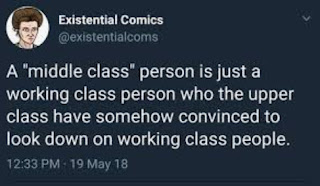

The democracy which we are taught to believe is inviolate and which left-wing Labour members spend such an inordinate amount of time working to uphold, is not the answer it is part of the problem. So long as we have massive inequalities in life chances and influence then Parliament exists to maintain a social system that benefits not just a few very rich people but also a large middle class who can both have very comfortable lives and convince themselves that they are better morally and politically than those below them.

I will confess here that I am lucky enough to be fairly comfortable, not rich, but I can get by. But, I have not forgotten that I came from a council estate, that I worked on building sites and in factories, that I spent a period unemployed and reliant on benefits or, more importantly, the condescension I received from middle class people who treated me as a moron because I was driving a van for a living. My heart and soul remains with the 14.6 million people in the UK living in poverty, with those being harassed by the DWP, and those who, mostly for reasons over which they have no control, are homeless or forced to use food banks.

Democracy is important but until we are able to move toward a form of democracy that is more than the opportunity to change your oppressor every few years, the vested interests will continue to control the public discourse and make any move toward a genuine socialism continue to sound as probable as the British royal family being sanctioned by the DWP for failing to find real jobs.