Last week Jonathan Reynolds, Labour's Shadow DWP Secretary gave an interview to Politics Home. It was pretty unremarkable as Labour interviews tend to be these days. But, one thing he said sent shockwaves throughout progressives in the party. Talking about reforming welfare, should Labour gain office (in 2024), he remarked that the more people put in to the system, the more they should expect to get out. The implication being that a system that treated everybody the same was inherently unfair.

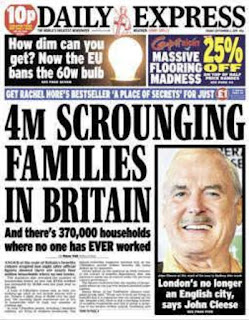

There can be little doubt that welfare is, or at least has been, one of the major fault lines separating Conservatives and Labour. There is also little doubt that many voters regard welfare payments as too generous. According to the British Social Attitudes surveys a consistent one-third of the British public believe that many people on welfare don’t really deserve it. The sense of an entire class of people too feckless to work and living off benefits that "we" have to pay for is well established in UK political folklore.

This sense that benefits should go only to those that deserve them is not new. in 1834 the UK Parliament amended what were then known as the "Poor Laws" to specify precisely who should be helped. The Act pulled no punches:

(a) no able-bodied person was to receive money or other help from the Poor Law authorities except in a workhouse;

(b) conditions in workhouses were to be made very harsh to discourage people from wanting to receive help.

This Act was enacted to "punish" the poor who were generally regarded as having brought their poverty on themselves. Nobody is suggesting that Jonathan Reynolds is advocating a return to the days of the workhouse, but his assertion that some people get less out than they put in (the deserving poor) has to have as its logical counterpart the widespread belief that many people take a lot more out than they put in (the undeserving poor). And, every bar room bore can regale you with tales of people they know who are not only taking more than they are entitled to, but are also living a life of luxury at the taxpayers expense.

As Sherry Linkon notes there has been a plethora of right-wing commentators quick to point the finger at the poor:

“Poor and working-class people, some critics argue, contribute to their troubles by not having stable marriages, giving birth to too many children from too many fathers, not being reliable workers, and over-indulging in drugs and alcohol. They focus on momentary pleasures rather than long-term planning, and parents aren’t sufficiently willing to sacrifice to improve their children’s lives.”

The clear implication of this demonisation of the poor is that if they tried a bit harder they could escape their conditions. Running in tandem is the belief that those who are doing quite well out of the system as it is are there through their talent and hard work. This was a belief held, for example, by right-wing sociologist Peter Saunders. In other words, the answer to poverty is simply to try harder, though if you lack the talent all that effort is going to leave you disappointed.

The appeal of these ideas, especially for middle class people, is that it ignores structural inequality in favour of a belief in meritocracy. And, interestingly enough, those who believe this nonsense can usually point to a few exceptionally talented individuals from lower class backgrounds who, through sheer will power have climbed the ladder.

But, for far too many people it's not a case of climbing the rungs but the problem that the rungs have been removed entirely. According to the United Nations some 14 million people in the U.K. are living in poverty. Do they deserve to be there? Is their place in society just the result of bad choices they have made? The Children's Society estimates that 4 million children are in poverty. What this means in practice is that they live in sub-standard housing, are malnourished and lack the "social capital" which children from better off households take for granted. Did those 4 million children choose their parents or make bad decisions that put them in poverty?

A 2007 Joseph Rowntree Foundation report found that poverty, whilst present in all ethnic groups, was greatest amongst black and minority ethnic groups. Whilst the rate for whites was 20%, among Bangladeshis it was 65% and among those identifying as Black African 45%. Are we to believe that BAME individuals are less talented? Or, that they are less hard working than whites? Or, are we seeing the result of systemic discrimination and inequality? In a week where Black Lives Matter has been on every front page surely we must see a connection between poverty and all the other social ills that, according to the United Nations, have been the result of deliberate policies pursued by successive British governments?

|

| Ex DWP Secretary took the fall for ex-Home Secretary |

It’s worth reminding ourselves of what Philip Alston actually said:

“The United Kingdom, the world’s fifth largest economy, is a leading centre of global finance, boasts a “fundamentally strong” economy and currently enjoys record low levels of unemployment. But despite such prosperity, one fifth of its population (14 million people) live in poverty. Four million of those are more than 50 per cent below the poverty line and 1.5 million experienced destitution in 2017, unable to afford basic essentials.”

He continued:

“There has been a shocking increase in the number of food banks and major increases in homelessness and rough sleeping; a growing number of homeless families – 24,000 between April and June of 2018 – have been dispatched to live in accommodation far from their schools, jobs and community networks; life expectancy is falling for certain groups; and the legal aid system has been decimated, thus shutting out large numbers of low-income persons from the once-proud justice system.”

He concludes:

“The philosophy underpinning the British welfare system has changed radically since 2010. The initial rationales for reform were to reduce overall expenditures and to promote employment as the principal “cure” for poverty. But when large-scale poverty persisted despite a booming economy and very high levels of employment, the Government chose not to adjust course. Instead, it doubled down on a parallel agenda to reduce benefits by every means available, including constant reductions in benefit levels, ever-more-demanding conditions, harsher penalties, depersonalization, stigmatization, and virtually eliminating the option of using the legal system to vindicate rights.”

This is a damning indictment of British social policy over the past 10 years. In any reasonably civilised society it would have produced a period of soul searching and a movement agitating for reform. Instead, Brexit obsessed Britain simply ignored the whole thing and carried on as if the UN report had never happened. The final nail in the coffin was in December when enough of the British electorate chose to turn their backs on the poor and disenfranchised and to reward a Tory government that have been quietly carrying out what can best be described as "social genocide".

When Theresa May was Home Secretary she famously introduced the "hostile environment "in order to discourage "illegal" immigrants. Her successor Amber Rudd was forced to resign when it became public knowledge that amongst those being deported were what is now known as the "Windrush Generation" many of whom arrived in Britain in the 1960’s without papers. But, the idea of a hostile environment is nothing new.

The 1834 Poor Laws were intended to create a hostile environment encouraging people to avoid poverty. In reality avoiding poverty, then as now, is done by accepting low wages. In 2019, the Office for National statistics calculated that wages were 2.9% lower than they had been in 2008. In the year up to April 2019, 37.5 % of full-time employees experienced a real-term cut in pay. For many people their net pay does not cover all their out-goings.

In addition, the number of part-time workers has increased from 6.63 million in 1997 to 8. 9 million in 2019. For many people part-time working suits their circumstances, but one group are disproportionately likely to be in part-time employment, and there's no prizes for guessing who: 40% of women are part-time compared to 13% of men. At the same time there has been a decline in male full-time employment. What this means is that more families are being drawn into a welfare system that the Tories are intent on destroying and Labour are, at best, equivocal about.

When Jonathan Reynolds says that people should be able to get out what they put in from the welfare system the suggestion is that some people are in need of benefits through their own fault. For example, people who take on too much debt and then lose their jobs should surely not be entitled to expect help paying their debts? Surely it must be that debtors have caused their own poverty.

In the 1800's it was common practice to put debtors in prison. If a person was well connected their stay would be relatively comfortable until a friend or relative could pay off their debt. For those less fortunate conditions were somewhat harsher:

“Conditions for debtors who could not raise money were appalling, with whole families cramped into overcrowded, cold, damp cells. Both women and men could find themselves imprisoned after falling into poverty.”

What we might note here is that there was certainly one law for the well connected and another for the poor. But, also and perhaps more relevant was that individuals who were in debt (and not from "good" families) were seen to deserve to be punished and their punishment was to serve as a warning to others.

In the UK in 2020 it was estimated by the Money Charity that the average household in the UK was £60,000 in debt. This figure is 12% higher than average earnings. What this means is that the average household in the UK does not earn enough each year to clear its debt and that year-on-year household debt is continuing to rise. The Office For Budget Responsibility has forecast that personal debt will rise From £2.068 trillion in 2018-19 to £2.425 trillion in 2023-24. Inevitably, as wages continue to fall, and prices continue to rise more and more households will be forced to rely on welfare to close the gap. The question is: do these people deserve help? Are they not just victims of their own bad choices?

I have accused Labour since Keir Starmer became leader of being too timid, and effectively providing no opposition at all. Jonathan Reynolds, like Starmer, was on Jeremy Corbyn's front bench. Like Starmer he lacks the radicalism which attracted 13.4 million people to Corbyn's Labour. Like Starmer he is prepared to criticise the Tories but only in hushed tones. If he is angry that 4 million children in the UK are living in poverty or that homelessness or food bank usage is growing, he hides it well. His ideas on benefits, such as they are, have the look and feel of the liberal reformer.

As he told Politics Home:

“One of the reasons that support for social security has diminished amongst parts of the country is the sense that people put into the system and they don’t get anything out of it. In a way, if you look at eligibility for Universal Credit, people are not wrong. You can make significant contributions to the system and find that actually, you’re not really eligible for any major support if you need it, even in a crisis like this one.”

Whilst there may be an element of truth in this it misses more than it hits. Of course, when people are working and paying taxes they expect that help will be there when they need it. But most people, most of the time do not think about benefits at all. If they think about those on benefits too often they fall back on lazy stereotypes. The blog "Poor side of Life" written by Charlotte Hughes, a young woman from Ashton-Under-Lyme details week after week the reality of life on benefits. Her problem is not just an unfair system, but the lack of empathy shown by DWP staff:

“Apparently the DWP know better than a doctor and a specialist doctor. They want everyone to look for non- existent jobs despite the fact that many aren’t able to work.”

The DWP treats everybody as essentially undeserving and are driven not by a desire to help people but to punish them, using the flimsiest of excuses to impose financial sanctions whose goal seems to have more to do with saving money than helping people into work. Such a system cannot be reformed as Labour now want, it has to be dismantled.

Let’s be clear, the vast majority (I’m talking 99.9%) of claimants do not want to be on benefits. Those capable of working would far rather be earning a wage. Our economy has been engineered to create a layer of available cheap labour to be deployed or not. It is not as simple as simply finding a job.

I well remember my time being unemployed. People I knew who were in work would offer me advice on how they would cope with unemployment. It ranged from finding a job abroad to starting their own business to training for a new career. None of them would be prepared to live on benefits which they clearly saw as a form of scrounging. None of them had the slightest clue what being unemployed really meant. For starters the lack of resources to leave the country (even if I felt I could find a job in a country where I didn't even speak the language) or to start a business (the very act of which would have prevented me claiming dole) or knowing exactly what to train for. And, these were supposed to be my friends!

Then, as now, a hostile environment existed for benefit claimants. Then, as now, people outside the benefit system felt it was over-generous and gave lazy people an excuse not to work. And, then as now, people in work had no appreciation of the state of the labour market. All of this was/is supported by newspaper headlines that talk of "scroungers" and "benefit fraudsters".

It perhaps should come as no surprise that, according to 2017 figures, the DWP employed 4,045 people to investigate benefit fraud, whilst HMRC employed just 522 to investigate tax evasion. The context here is all important. According to Full Fact an estimated £2 billion per year is fraudulently claimed in benefits; HMRC estimates that £1.7 billion in tax revenue was lost through avoidance in 2016/17, £5.3 billion was lost through differences in legal interpretation, and another £5.3 billion was through evasion.

The benefits system in the UK has always had a view of deserving and undeserving poor. This view is shared by journalists, politicians, and academics who propagate a set of beliefs about work and benefits that sees rich employers and landlords as "wealth creators" and those on benefits as "lazy scroungers" . That so many of these so called scroungers are from BAME communities, or from areas that have traditionally had high levels of deprivation gives little pause for thought. Underlying notions of deserving and undeserving poor is a pernicious myth of a meritocracy enabling social mobility. In this myth some combination of talent, hard work and sheer willpower catapults people to social success.

What the myth ignores, because it remains an inconvenient truth is that wealth, income and poverty are symbiotically connected. To be born wealthy (even moderately wealthy) is to be born into a society whose possibilities are constrained only by your own indolence (and in some cases not even that). On the other hand, to be born poor, even with talent and hard work in abundance is not just to be born with a glass ceiling but also glass walls.

The same opportunities that exist for the wealthy can be seen, and dreamed about, but cannot be accessed without first smashing through those walls. Occasionally doors are opened and a few of the poor are allowed to enter the World of the wealthy. Others can see them through the glass walls as they move away, and thus can have their own poverty reinforced as their own doing. After all, if they had really wanted it they too could have got through those doors. But, they were too busy drinking, taking drugs or simply existing to take what was on offer.

Labour's suggestion that the system can be reformed is predicated on the pessimistic belief that the poor will always exist and what those who deserve it need are payments that alleviate the worst of their suffering. Whilst alleviating suffering is better than exacerbating it, this has more to do with charity than rights. Until we begin to see "the poor" as people in their own right we will continue to see them as people who need our benevolence and charity. Inevitably, the language of deserving poor will continue to form part of that discussion. We need to start thinking of poverty as the problem to be solved, and that may require a radical re-think of our society. It may well require a change so fundamental that the entire system will need to change rather than just be amended. It could start if opposition MPs would stop invoking notions of deserving poor (even if by implication) and start declaring loudly and proudly that nobody deserves to be poor, and that not only do they oppose any and all welfare cuts in the here and now, their goal is nothing less than the total abolition of all poverty. And, if that means that the wealthy have to take a cut then so be it.

A very good piece indeed. Part of the problem is how Labour campaign against this problem of our time. It is half -hearted, uncoordinated and basically given lip service to, by Councillors, who should be playing a leading role in their communities highlighting poverty. This is missing sadly in to many communities. Its seems they feel its above their pay grade. Regional Offices that should be leading on issues like this and encouraging the development of training for members around these challenges have become bureaucratic offices that do not do politics.

ReplyDelete