At its annual conference the Labour Party announced a new commitment to provide personal care for all elderly people. Whilst this policy may not get the headlines amongst some other radical policies, it has the potential to really change the lives of people currently coping with the twin difficulties of an unexpected and debilitating illness and a punitive DWP philosophy which is seeing claimants literally driven to suicide.

It is estimated that there are currently around 850,000 people in the UK with dementia. This means that there are a further 850,000 partners who suddenly find themselves as carers at a time in their lives when they had expected to enjoy their twilight years as a couple. Yet, once a diagnosis of dementia is given the responsibility of the state seems to end.

|

| My father served in the Royal Navy during WW2 |

My father is 93 years old, fought in the Second World War, worked for the rest of his life, and never took a day off through illness. He is now forced to live in a “care home” because my Mother, herself 89, simply could not cope with the demands placed upon her of his dementia.

I use inverted commas around the words care home because, despite my mother using the majority of her savings to put him in an expensive home, from what I can see what the owners of the home care most about is their profit. This is not to say that the staff do not care, they clearly do, but that the overall aim of the company is to reward its shareholders, not its employees.

Is it a home? In a recent conversation my father described it to me as “like a prison”. He clearly understood that it was not a prison, but like all institutions it is regimented. There is little choice afforded to residents who have to fit in with the institutional demands of set meal times, bed times, washing times etc. Of course, from the perspective of the institution regulation allows for the organisation of the working day. But for the individuals subjected to this the ability to choose, for example, to have a lay in or stay up late, is totally absent. In such an environment people become institutionalised.

|

| Dementia is a progressive disease |

People with dementia are often treated as if the diagnosis itself steals their personality. They are treated as if they have no agency, no ability to choose between competing options and no right to be treated with dignity. That tendency may exist among family members, particularly as the disease progresses, but it is

prevalent among carers who, despite

their best intentions, almost inevitably find themselves infantilising their charges. That is not a criticism of individual staff many of whom are very dedicated but it is easy to slip into a parental role when a person

cannot dress themselves, feed themselves or go to the toilet. Their humanity can be undermined by processes designed to assist them.

For dementia sufferers in their own home the demands upon their nearest and dearest are huge. From having a partner who has opinions and can make

decisions the partner finds themselves recast as carer. This role may be easy for some and almost impossible for others. But even for the saintly the importance of the Labour Party policy cannot be understated. Currently there are benefits for carers but these are, essentially, a pittance. Around £81 a week.

Compare the benefits with the cost of buying in support. A home package can cost as much as £400 per week whilst an institution will cost upwards of £1000 per week.

|

| Cate providers are big business |

According to a report in the Guardian some 84% of the care industry is now in private hands. One such company is Barchester which, according to a report in the Financial Times, owns over 200 homes, employs 17,000 staff and houses 11,000 elderly residents. Barchester, along with many of the private

care suppliers, was recently put up for sale by the three horse racing tycoons who own it. It’s price? £2.4 billion. If that sounds incredible it’s annual profits are close to £165 million and rising year on year.

Barchester was considered to be particularly attractive because many of its residents are paying privately rather than relying on local authority funding. Costs for long-term care are upwards of £1200 per week, which is over £62,000 per year.

You might think that you would have to be incredibly rich to afford such a cost. My parents are far from rich. As I think I’ve mentioned before I was born in a council house. My Dad worked for a fruit and veg wholesaler and by the end of his working life earned a little above the average wage. He did not have a generous private pension, but because my parents had managed to save a little over their lifetime their entire savings are now being whittled away very quickly by care costs.

Currently there is no state support for anybody with savings over £23,600. The

cost of dementia care is falling disproportionately on ordinary people who have

tried to save a little for their old age. The beneficiaries of this are companies like Barchester who milk every penny they can to provide only basic care.

Labour’s policy to provide a personal care package for all elderly people is welcome. It would mean that everybody over 65 would be able to access care in their own homes to assist them in their daily routines and allow the elderly to retain their dignity. Labour has also pledged to bring social care back under local authority control and end the use of zero hour contracts.

It is certainly a radical start but as both the Kings Fund and the Nuffield Centre have pointed out it does not go far enough. Of course, if Labour were to go further they would face endless questions about the affordability of their plans, so politically establishing the principles may be more important than the detail.

For myself, and drawing on my own experiences, I would suggest the following reforms. First, social care should be brought within the NHS, perhaps in partnership with local authorities. Healthcare should be based on need not profit or ability to pay. Staff should be both properly remunerated and trained. Given the scale of the problem we need far more care staff than we currently have. Support packages for carers need to be integral to the reforms. Currently organisations such as the Alzheimer’s Society and individuals such as dementia sufferer Wendy Mitchell do a fantastic job of providing support, but respite and education for carers is every bit as important as the care provided for the victims of a disease such as dementia.

I know from personal experience how devastating the diagnosis can be. My mother has struggled to understand what is happening to the husband she has loved since she was 16 and to the life she thought they would live out together.

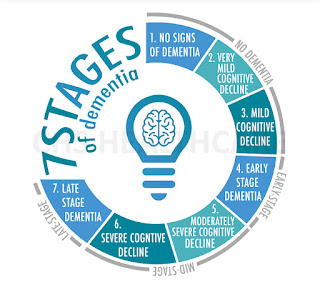

For the medical profession the diagnosis is the end, for the sufferer and their families it is just the beginning. The dementia journey can be a long and tortuous one. Carers need support but they also need to understand what is happening.

We live in one of the richest countries in the World. The elderly have played a major part in creating the wealth and opportunities we all take for granted. We should not discard them because they are no longer economically active. They have done their part to provide for us, it is now our turn to care for them. That is not just a socialist demand but a human one.

According to a report in the Guardian some 84% of the care industry is now in private hands. One such company is Barchester which, according to a report in the Financial Times, owns over 200 homes, employs 17,000 staff and houses 11,000 elderly residents. Barchester, along with many of the private

care suppliers, was recently put up for sale by the three horse racing tycoons who own it. It’s price? £2.4 billion. If that sounds incredible it’s annual profits are close to £165 million and rising year on year.

Barchester was considered to be particularly attractive because many of its residents are paying privately rather than relying on local authority funding. Costs for long-term care are upwards of £1200 per week, which is over £62,000 per year.

You might think that you would have to be incredibly rich to afford such a cost. My parents are far from rich. As I think I’ve mentioned before I was born in a council house. My Dad worked for a fruit and veg wholesaler and by the end of his working life earned a little above the average wage. He did not have a generous private pension, but because my parents had managed to save a little over their lifetime their entire savings are now being whittled away very quickly by care costs.

Currently there is no state support for anybody with savings over £23,600. The

cost of dementia care is falling disproportionately on ordinary people who have

tried to save a little for their old age. The beneficiaries of this are companies like Barchester who milk every penny they can to provide only basic care.

Labour’s policy to provide a personal care package for all elderly people is welcome. It would mean that everybody over 65 would be able to access care in their own homes to assist them in their daily routines and allow the elderly to retain their dignity. Labour has also pledged to bring social care back under local authority control and end the use of zero hour contracts.

It is certainly a radical start but as both the Kings Fund and the Nuffield Centre have pointed out it does not go far enough. Of course, if Labour were to go further they would face endless questions about the affordability of their plans, so politically establishing the principles may be more important than the detail.

For myself, and drawing on my own experiences, I would suggest the following reforms. First, social care should be brought within the NHS, perhaps in partnership with local authorities. Healthcare should be based on need not profit or ability to pay. Staff should be both properly remunerated and trained. Given the scale of the problem we need far more care staff than we currently have. Support packages for carers need to be integral to the reforms. Currently organisations such as the Alzheimer’s Society and individuals such as dementia sufferer Wendy Mitchell do a fantastic job of providing support, but respite and education for carers is every bit as important as the care provided for the victims of a disease such as dementia.

I know from personal experience how devastating the diagnosis can be. My mother has struggled to understand what is happening to the husband she has loved since she was 16 and to the life she thought they would live out together.

For the medical profession the diagnosis is the end, for the sufferer and their families it is just the beginning. The dementia journey can be a long and tortuous one. Carers need support but they also need to understand what is happening.

We live in one of the richest countries in the World. The elderly have played a major part in creating the wealth and opportunities we all take for granted. We should not discard them because they are no longer economically active. They have done their part to provide for us, it is now our turn to care for them. That is not just a socialist demand but a human one.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Many thanks for reading this post and for commenting.